.

This post contains a detailed summary of the tranche of National Curriculum Review and associated publications released on 7 February 2013. It examines the implications of the changes proposed, including the impact on high-attaining gifted learners.

This is the latter part of a bigger study of the National Curriculum Review since the first Government response in June 2012.

This is the latter part of a bigger study of the National Curriculum Review since the first Government response in June 2012.

Part One itemises the issues outstanding following that initial response and offers a narrative-cum-commentary on subsequent developments, up to the day before publication of the second response.

Part Two sets this new compendium of documents in the context of earlier progress, considering whether they properly address the outstanding points following the June 2012 announcement, as well as those emerging from subsequent developments.

?.

The Oral Statement

During the evening of 6 February, rumours began to emerge on Twitter that a National Curriculum Review announcement would finally be made the following day, some eight months on from the previous announcement.

.

.

There was some scepticism given the number of times the announcement had apparently been delayed in the past. But, by the morning, there were press stories from normally reliable sources including The Independent, The Guardian and the BBC. (These links go to updated versions of the original articles).

The Secretary of State duly made his statement to Parliament at 11.30am that morning and his Department released the associated documentation as soon as he had finished speaking. A parallel statement was delivered in the House of Lords that afternoon.

The statements summarise the changes proposed, concentrating primarily on Key Stage 4 reforms. Mr Gove said that:

- Consultation supported the case for changes to GCSE examinations, but the plan to introduce English Baccalaureate Certificates (EBCs) ? with single exam boards offering completely new exams in specified subjects ? had proved ?a bridge too far?.

- The Government would concentrate instead on GCSE reform. GCSEs should be linear qualifications with all exams normally taken at the end of the course; there would be assessment of extended writing in subjects such as English and history; in maths and science there would be greater emphasis on quantitative problem-solving; internal assessment and use of exam aids would be minimised.

- GCSEs would remain ?universal qualifications? ? the Government would expect ?the same proportion of pupils to sit them as now?. But students would not be ?forced to choose between higher and foundation tiers?.

- There would be new GCSEs in English, maths, the sciences, history and geography, these to be in place for teaching to begin at the start of academic year 2015/16.

Little of value emerged from the brief debates that followed. The Labour Opposition called the announcement ?a humiliating climbdown? and pressed for cross-party consensus on future arrangements.

When challenged as to why he had not acted sooner, the Secretary of State said only that:

?I was clear that the programme of reform we put out in September was ambitious, and I wanted to ensure that we could challenge the examinations system?and, indeed, our schools system?to make a series of changes that would embed rigour and stop a drift to dumbing-down. I realised, however, as I mentioned in my statement, that the best was the enemy of the good. The case made by Ofqual, the detail it produced and the warning it gave, as well as the work done by the Select Committee, convinced me that it was better to proceed on the basis of consensus around the very many changes that made sense rather than to push this particular point.?

This suggests that it was the combined weight of Ofqual and the Select Committee ? rather than the outcomes of consultation ? that ultimately caused the volte face.

.

.

The Documents

The documentation can be divided into three subsets, relating to the National Curriculum, Key Stage 4 Reform and changes to the secondary accountability system respectively.

I have included below hyperlinks to all relevant publications available on the Department for Education?s website:

.

Material relating to the National Curriculum itself

A home page carries links to The Consultation on the Draft National Curriculum Programmes of Study

This in turn provides links to:

- An associated publication ?The National Curriculum in England ? Framework Document for Consultation? which contains overarching statements that apply to the curriculum and National Curriculum as a whole, as well as draft programmes of study and attainment targets for each National Curriculum subject (excluding the proposed programmes of study for KS4 English, maths and science). Each subject-specific draft programme of study (apart from KS4 English, maths and science) can be obtained from a separate page. Hyperlinks to each are included in the commentary below.

- Separate initial draft programmes of study for KS4 English, maths and science. The associated commentary says ?further versions will be developed alongside work on reformed GCSEs in these subjects and a formal consultation on the drafts will take place later in the year?.

.

Material Relating to GCSE Reform

This comprises:

.

Material Relating to Secondary Accountability

A new Consultation Document on Secondary School Accountability on which responses are due by 1 May 2013.

This refers to an upcoming parallel consultation on primary sector accountability which has not yet been published (and no specific date is given for its publication).

There is (as yet) no additional overarching commentary from DfE ? such as a Q and A brief ? to help readers interpret these documents and understand the connections between them. Such material may be added in the next few weeks as the consultation progresses and issues emerge from the various commentaries that are published.

.

The National Curriculum Reform Proposals

.

National Curriculum Structure

The consultation document on National Curriculum Reform makes a familiar two-fold case for change: comparison with the best performing jurisdictions worldwide and research evidence of deficiencies in existing arrangements.

It sets out plans for:

- Retention of the current subject composition of the National Curriculum (apart from the relatively minor changes below) and of the existing Key Stage structure.

- Greater rigour in English, maths and the sciences, compulsory study of a foreign language at Key Stage 2 and a new Computing programme of study replacing ICT.

- Apart from primary MFL and Computing, no further changes to the required foundation subjects. KS4 students will still have access to subjects within each of the four defined ?entitlement areas?.

- Detailed programmes of study in the primary core subjects to give teachers ?a detailed guide?to support them in bringing about a step-change in performance in these vital subjects? while others ?give teachers more space and flexibility to design their lessons by focusing only on the essential knowledge to be taught in each subject.?

- Informal consultation on the draft KS4 programmes of study in English, maths and science ? because they require further consideration alongside new subject content requirements for reformed GCSEs in these subjects. Statutory consultation will not begin until those GCSE content requirements are published. These core KS4 programmes of study will not be introduced until 2015, alongside the reformed GCSEs.

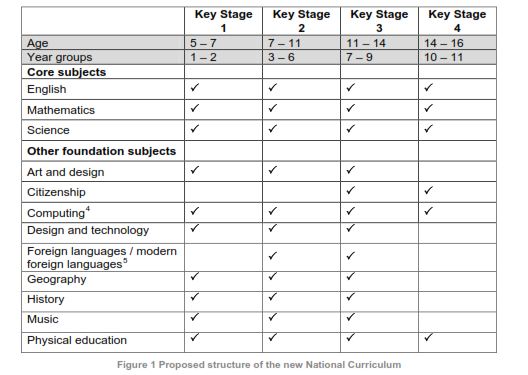

The Framework Document includes a helpful diagram showing the proposed structure of the new National Curriculum by Key Stage.

.

?.

Aims

The Framework Document describes the relationship between the National Curriculum and wider school curriculum, sets out proposed aims for the National Curriculum and draft statements on inclusion and on cross-curricular language, literacy and numeracy.

The draft Aims are very brief and emphasise knowledge over skills:

?The National Curriculum provides pupils with an introduction to the core knowledge that they need to be educated citizens. It introduces pupils to the best that has been thought and said; and helps engender an appreciation of human creativity and achievement.

The National Curriculum is just one element in the education of every child. There is time and space in the school day and in each week, term and year to range beyond the National Curriculum specifications. The National Curriculum provides an outline of core knowledge around which teachers can develop exciting and stimulating lessons.?

As well as seeking comments on the draft aims, the Consultation Document advances the suggestion that additional subject-specific aims are unnecessary and could be dispensed with, so teachers could form their own instead.

.

Draft Programmes of Study and Attainment Targets

The Consultation Document seeks comments on the content of the draft programmes of study and whether it represents ?a sufficiently ambitious level of challenge for pupils at each key stage?.

In relation to attainment targets the document says:

?The Government has already announced its intention to simplify the National Curriculum by reforming how we report progress. We believe that the focus of teaching should be on subject content as set out in the programmes of study, rather than on a series of abstract level descriptions?

A single statement of attainment that sets out that pupils are expected to know, apply and understand the matters, skills and processes specified in the relevant programme of study will encourage all pupils to reach demanding standards. Parents will be given clear information on what their children should know at each stage in their education and teachers will be able to report on how every pupil is progressing in acquiring this knowledge.

We are currently seeking views on how to improve the accountability measures for secondary schools in England?Approaches to the assessment of pupils? progress and recognising the achievements of all pupils at primary school will be explored more fully within the primary assessment and accountability consultation which will be issued shortly.?

Comments are invited, meanwhile, on the proposed wording of the attainment targets which seem to be identical for each subject and are essentially vacuous:

?By the end of each key stage, pupils are expected to know, apply and understand the matters, skills and processes specified in the relevant programme of study.

There is a question asking whether consultees agree that the draft programmes of study provide for effective progression between key stages. They are also asked whether they agree with the proposed introduction of computing in place of ICT.

.

Inclusion Statement

Another question asks whether the National Curriculum embodies ?an expectation of higher standards for all children? and comments are invited on the impact on ?protected characteristic groups? (a footnote explains that these cover disability, ethnicity, gender, sexual identity, gender identity, religion or belief and, for workforce issues, age).

Comments are not explicitly invited on the text of the draft inclusion statement, which is reproduced in full below:

?Setting suitable challenges

Teachers should set high expectations for every pupil. They should plan stretching work for pupils whose attainment is significantly above the expected standard. They have an even greater obligation to plan lessons for pupils who have low levels of prior attainment or come from disadvantaged backgrounds. Teachers should use appropriate assessment to set targets which are deliberately ambitious.

Responding to pupils? needs and overcoming potential barriers for individuals and groups of pupils

Teachers should take account of their duties under equal opportunities legislation that covers disability, ethnicity, gender, sexual identity, gender identity, and religion or belief.

A wide range of pupils have special educational needs, many of whom also have disabilities. Lessons should be planned to ensure that there are no barriers to every pupil achieving. In many cases, such planning will mean that these pupils will be able to study the full National Curriculum. The SEN Code of Practice will include advice on approaches to identification of need which can support this. A minority of pupils will need access to specialist equipment and different approaches. The SEN Code of Practice will outline what needs to be done for them.

Many disabled pupils have little need for additional resources beyond the aids which they use as part of their daily life. Teachers must plan lessons so that these pupils can study every National Curriculum subject. Potential areas of difficulty should be identified and addressed at the outset of work.

Teachers must also take account of the needs of pupils whose first language is not English. Monitoring of progress should take account of the pupil?s age, length of time in this country, previous educational experience and ability in other languages.

The ability of pupils for whom English is an additional language to take part in the National Curriculum may be in advance of their communication skills in English. Teachers should plan teaching opportunities to help pupils develop their English and should aim to provide the support pupils need to take part in all subjects.?

.

Other Issues, Implementation and Timetable

Strangely there is no separate question seeking comments on the draft statement about language, literacy and numeracy across the curriculum.

There is, however, a generic question about the extent to which the National Curriculum ?will make clear to parents what their children should be learning at each stage of their education?, plus questions about key factors that may impact on effective implementation in schools and about sources of support that schools will need.

The Document acknowledges that there are ?mixed views? about whether to phase in the new arrangements. It has concluded that September 2014 should be the default except where Key Stage 4 reforms justify a longer timescale. KS4 English, maths, science, history and geography will be introduced from September 2015 but ?Changes to remaining subjects will follow as soon as possible after that?.

There is a proposal to disapply large parts of the existing National Curriculum from September 2013: schools will still need to teach the subjects, but not the prescribed content.

This would apply to English, maths and science in Years 3 and 4 and all foundation subjects throughout KS1 and KS2. Disapplication is intended to ?give schools greater freedom to adapt their own curricula?.

Similarly, the current programmes of study for all KS3 and KS4 subjects would be disapplied from September 2013 ? this to continue until the new programme of study comes into force for each relevant year group.

Consultees are asked whether they agree with such disapplication.

There is some disagreement between the two documents over the timetable. The introduction to the Framework Document says:

?Subject to Ministers? final decisions, and to the approval of Parliament, it is the Government?s intention that the final version of this framework will be published in the autumn of 2013, and that the elements that require statutory force will come into effect from September 2014.?

The use of the phrase ?autumn of 2013? suggests that the standard 12-month period for schools to prepare may be somewhat eroded.

But, according to the Consultation Document, results of the consultation and the Department?s response will be published over the summer and the final National Curriculum will be available ?early in the autumn term? (so is more optimistic than the Framework Document that schools will have close to a full year to prepare for introduction from September 2014).

.

Subject-specific draft Programmes of Study

It is not possible in the space available to provide a thorough analysis of each draft Programme of Study, but here are very brief snapshots of each.

Incidentally, it is unclear whether the drafts PoS for English, maths and science at KS1-2 are identical to those issued in June 2012 or have been further revised.

- English KS1-2 (40 pages) is also accompanied by an Appendix ?(22 pages). This is actually two appendices, covering spelling and grammar and punctuation respectively. The former includes statutory spelling lists as well as non-statutory guidance. There is also a separate non-statutory Glossary (18 pages) described as ?an aid for teachers?. The three combined add up to 80 pages, making them comfortably the longest subject-specific package. The PoS is hugely detailed, set out on a year-by-year basis, together with extensive non-statutory ?notes and guidance?. There is a separate section on Spoken Language and the PoS contains the expected emphasis on phonics and learning poetry by heart.

- English KS3 (7 pages) is positively sketchy by comparison. The requirements for Reading include: ?a wide range of fiction and non-fiction, including in particular whole books, short stories, poems and plays with a wide coverage of genres, historical periods, forms and authors. The range should include high-quality works from: English literature, both pre-1914 and contemporary, including prose, poetry and drama; Shakespeare (at least one play); seminal world literature, written in English?. There is an additional requirement to study at least two writers in depth each year.

- English KS4 (8 pages) is similarly brief. The Reading requirement includes: ?studying high-quality, challenging, whole texts in detail including: two plays by Shakespeare; representative Romantic poetry; a nineteenth-century novel;? representative poetry of the First World War; British fiction, poetry or drama since the First World War; seminal world literature, written in English.?

- Maths KS1-2 (44 pages) is again extremely detailed. It, too, is set out on a year-by-year basis and includes much non-statutory material ?notes and guidance?. There are specific sections on Spoken Language and ICT (?calculators should not be used as a substitute for good written and mental arithmetic?).

- Maths KS3 (9 pages) is much shorter. It includes clear reference to problem-solving within the curricular aims and an introductory section which effectively covers mathematical skills.

- Maths KS4 (10 pages) is much the same, with similar references to problem-solving and mathematical skills.

- Science KS1-2 (39 pages) is similar in style to the draft PoS for English and maths. It too includes a discrete section about Spoken Language.

- Science KS3 (15 pages) covers Biology, Chemistry and Physics as well as generic scientific skills and attitudes.

- Science KS4 (18 pages) also covers Biology, Chemistry and Physics plus generic scientific skills and attitudes. In biology there is explicit reference to ?the evolution of new species over time through natural selection? and ?the evidence for evolution from geology, fossils, comparative anatomy and molecular biology?.

- Art and Design KS1-3 (6 pages) makes no reference to talent development. There is reference to ?the greatest artists, architects and designers in history? but no specific periods or artists are compulsory.

- Citizenship KS3-4 (6 pages) includes UK governance and political system as well as volunteering and financial education. At KS3 there is an odd reference to ?the precious liberties enjoyed by the citizens of the United Kingdom?.

- Computing KS1-4 (7 pages) draws together computer science and information technology. The KS4 PoS seems unusually brief and is much less specific than those for KS2 and KS3.

- Design and Technology KS1-3 (8 pages) has curricular aims that highlight cookery, food and nutrition above other areas and include the history of design and technological innovation.

- Geography KS1-3 (7 pages) shows a reasonable balance between knowledge and skills within the subject aims. Press attention has focused on the removal of references to the European Union.

- History KS1-3 (10 pages) has attracted most comment. The subject aims include both knowledge and skills. At KS1, all named historical characters are given as examples. KS2 expects a chronological treatment of British history from the Stone Age to the Glorious Revolution. Named individuals required to be covered are: Pepys, Cromwell, Caxton, Wycliffe, Chaucer, Llewellyn, Dafydd ap Gruffyd, Robert the Bruce, William Wallace, de Montfort, Thomas Becket and various kings, queens and emperors. KS3 requires coverage of ?The development of the modern nation? (General Wolfe to the Boer Wars) and ?The twentieth century?. Named individuals required to be studied include: Wolfe, Clive, Bacon, Locke, Wren, Newton, Adam Smith, Nelson, Wellington, Pitt, Olaudah Equiano, Gladstone, Disraeli, Chamberlain, Salisbury, Lloyd George, Churchill, Roosevelt, Stalin, Atlee, Gandhi, Nehru, Jinnah, Kenyatta, Nkrumah, Attlee, Thatcher. May Seacole is exemplary only (ie preceded by a ?such as?). There is a strong emphasis on British (primarily English) history throughout.

- Foreign Languages KS2-3 (7 pages). The ?Purpose of study? includes opportunities to ?read great literature in the original language?. The languages specified are French, German, Italian, Mandarin, Spanish, Latin or Ancient Greek. Spoken language requirements do not apply to the ancient languages.

- Music KS1-3 (6 pages) contains no requirements to study specific musical genres or composers and there is no reference to talent development.

- Physical Education KS1-4? (8 pages). There is reference to competitive sport, dance, outdoor activities, swimming. Only at KS4 is there reference to ?becoming a specialist or elite performer?. This reference seems inconsistent since there are no comparable statements in other subjects such as art and music.

The contrast between the last of these ? 8 pages covering all four Key Stages ? and the first ? 80 pages covering just two Key Stages ? is hugely marked. The brevity of the PE PoS will become even more stark if subject-specific aims and the attainment target are stripped out.

This contrast illustrates perfectly the point made in Part One of this post, that there will be inevitable pressure during consultation to add detail to the over-brief PoS and, conversely, to strip it from the over-detailed PoS in the primary core.

.

Revised Proposals for Key Stage 4

The Secretary of State?s letter to Ofqual is a response to Ofqual?s earlier advice on the Government?s proposals for KS4 reform ? cited by the Secretary of State as influencing his decisions ? and contains his ?policy steers on the development of the new qualifications?.

These are very similar to those set out in the Oral Statement summarised above.

- The GCSE qualification will stay in place, though subject to significant reform. New-style GCSEs are to be ready for teaching from September 2015 in at least: English language, English literature, maths, biology, chemistry, physics, combined science (double award), history and geography. The aim should be for all subjects to be ready for teaching from September 2016 if possible. Ofqual should give schools at least a year?s familiarity with revised regulatory requirements before they start teaching the new-style qualifications.

- There should no longer be a combined English option and all combined science options should be worth two GCSEs. Further advice will follow about ?the subject suite in mathematics?. There are no plans to publish content requirements for subjects outwith the EBacc.

- GCSEs will continue as the basis on which schools will be held accountable for the performance of all their pupils. But the value for individuals ?must take precedence ahead of ensuring the absolute reliability of the assessment?.

- ?I am persuaded by your advice that we should not move to a single Awarding Organisation offering each subject suite at this time? but the position will be kept under review.

- Ofqual will want to take proposals for the new accountability system into consideration when designing new regulatory arrangements.

- GCSEs should remain ?universal qualifications of about the same size as they are currently, and accessible, with good teaching, to the same proportion of pupils as currently sits GCSE exams at the end of Key Stage 4?. But there must be ?an increase in demand? at Grade C ?to reflect that of high-performing jurisdictions?. At the top end there should be more challenging content and ?more rigorous assessment structures?.

- Reformed GCSEs should avoid higher and lower tier papers ?while enabling high quality assessment at all levels?. The approach will vary between subjects and ?a range of solutions may come forward? such as ?extension papers alongside a common core? (which is therefore not seen as two-tier). ?There should be no disincentive for schools to give an open choice of papers to their pupils?.

- GCSEs must test extended writing in subjects like English and history, have ?fewer bite-sized and overly structured questions?, and there should be more emphasis on quantitative problem-solving in maths and science. Internal assessment and use of exam aids should be kept to a minimum ?and used only where there is a compelling case to do so?.

- There is a strong case for a new grading scale and Ofqual advice is requested on this. Changes ?should differentiate performance more clearly, particularly at the top end?. For English and maths, pupils might receive more information direct from awarding bodies.

Ofqual has already responded to the Secretary of State?s letter. Although the letter is broadly positive, Ofqual clearly signal that the timetable is challenging, will need to be kept under review and, if necessary, delayed.

The Response to Consultation Document is relatively brief and adds little, but it does provide a useful context in which to consider the steers set out above.

A colossal 84% of respondents felt that the EBC proposals had not identified ?the right range of subjects?. Many said that the other subjects should not be devalued. There was significant opposition to the proposed ?Statement of Achievement?

Interestingly, it says that ?Nineteen per cent of respondents said that new qualifications should be comparable with international tests like PISA or with qualifications used in other high-performing jurisdictions.?

The discussion of tiering notes that:

?A small majority (56 per cent) of respondents said that it would not be possible to end tiering across the full range of English Baccalaureate subjects, with the remainder fairly evenly split between those who thought it was possible and those who were unsure. Those who felt it would not be possible were often unsure that a single exam could assess all abilities, while others felt that tiering works well or that removing it might impact disproportionately on low attaining pupils. We asked what approaches might enable tiering to be removed; the most frequently suggested methods were a wider range of questions and additional papers aimed at narrower ranges of abilities.

AOs [Awarding Organisations] said that there would be particular challenges with removing tiering from mathematics qualifications, but most said [apparently contradicting the preceding point] ?that it would be possible to develop qualifications which allowed all pupils to access all grades without using tiering. Some of the AOs spoke favourably of taking an approach where the qualifications are accessible to all pupils but may be taken at different ages depending on when each pupil was ready for them.?

Turning to internal assessment:

?Almost half of respondents said that none of the English Baccalaureate subjects could be entirely externally assessed, while a quarter said that all of them could be. Almost half of respondents thought that mathematics could be completely assessed externally, while around a third thought each of the other subjects could be entirely externally assessed. Practical science work was the aspect that was most commonly cited as requiring internal assessment, with oral ability in languages, English communication and geography fieldwork all identified by a significant number of people.?

As for the timetable for implementation:

?The majority (55 per cent) of respondents said that schools will need more than 18 months to prepare for new qualifications, while a further 23 per cent said that they would need between 12 and 18 months. Only five per cent of people said that schools could be ready in less than 12 months.?

The proposed timetable above still allows twelve months.

.

Proposals for Secondary Accountability Reform

The consultation document on Secondary School Accountability begins with a statement that the timetable will be determined in the light of responses ? with implementation of various elements in either 2015 or 2016.

The focus is exclusively on the publication and use of school performance data: there are no changes proposed to Ofsted inspection, though the document does consider how Ofsted will ?use the headline measures in its work?. The level at which floor targets are pitched is also not addressed: information will only be available once the reformed GCSEs have been further developed.

The aims and vision reintroduce the concept of a ?high autonomy, high accountability? system. The latter should be fair, transparent and:

?reward schools that set high expectations for the attainment and progress of all their pupils, provide high value qualifications, and teach a broad and a balanced curriculum?The aim of the changes to assessment and accountability is to promote pupils? deep understanding across a broad curriculum and maximise progress and attainment for all pupils. Central to this is the need to make it easier for parents and the public to hold schools to account.?

The introductory paragraphs refer to a new Performance Data Portal (see below) but: ?within this context, the school performance tables will continue to make key measures about all schools easily available?. These are the headline measures that most parents should be aware of and that Ofsted will use when judging schools? performance.

The case for change rests on the contention that there are perverse incentives in the current system, while the floor targets in particular tend to encourage schools to focus disproportionately on the D/C borderline.

Schools can also be encouraged to focus on a narrow curriculum and current arrangements may also:

?Adversely affect high attaining pupils. Ofsted have noted that some schools enter pupils for qualifications early to ?bank? a C grade, even though pupils would be better served by entering the qualifications later in the year and aiming for an A or B grade.?

The furore over GCSE English marking in summer 2012 is indicative of ?what can happen when qualifications are placed under particular pressure by the accountability system?.

There are six specific proposals:

.

First, to publish extensive data about secondary schools through a School Performance Data Portal, introduced in 2015, that ?will bring all the information about schools onto one accessible website?.

The portal (also called a ?Data Warehouse?) might be used to gather data from non-statutory tests deployed in secondary schools ? including commercially available tests ? and it ?may be possible? to enable schools to enter their own internal test data.

This might be helpful at KS3 where there is mandatory teacher assessment but parents do not receive test results. The Warehouse is described as helping parents contextualise the performance of their own children:

?Parents would then be able to understand the results they receive about their own child more easily, helping them to make an informed judgement about whether their child?s test results represent good progress or a cause for concern?

But exactly how this would happen ? given that individual pupils cannot be identified in publicly available data ? is not explained.

.

Second, to publish a threshold measure showing the percentage of pupils achieving a ?pass? [ie Grade C and above under current arrangements] in English and mathematics. This measure should be part of the floor standard.

This is justified on the grounds that the system should encourage schools to secure a good standard in key subjects amongst as many of their pupils as possible. A pass in English and maths is perceived as critical to pupils? subsequent progression.

Since the GCSE grading system will change and there is also pressure to raise the level of what constitutes a ?pass?, this is likely to be a more demanding threshold in future.

.

Third (and perhaps most critically) to publish an ?average point score 8? measure based on each pupil?s achievement across eight qualifications and comprising three components:

- Any combination of ?three other current EBacc subjects? (except that combined science cannot count alongside physics, chemistry or biology) (3).

- ?Three further high value qualifications?, whether in EBacc subjects, other academic subjects, arts subjects or vocational subjects that meet ?the Department?s pre-defined criteria? (3).

Schools will thus be incentivised to provide a broad and balanced curriculum ?including the academic core of the EBacc as appropriate?. If pupils take more than three further qualifications, their best three will count. Pupils need not take eight qualifications ? they may wish to concentrate on getting higher grades in fewer subjects.

The APS is expected to have currency amongst pupils:

?Pupils will know their own score, and will be able to evaluate how well they have performed at the end of Key Stage 4 by comparing their score with easily available local and national benchmarks.?

The consultation paper argues that:

?This approach incentivises schools to offer an academic core of subjects to their pupils, by reserving five slots for these qualifications. It allows schools flexibility to tailor the core as appropriate for their pupils. Including three further qualifications in the measure will reward schools that also offer a broad and balanced curriculum. Pupils can follow their interests to take further academic subjects, including but not limited to further EBacc subjects, arts subjects, and high value vocational qualifications.?

The point score system will not be developed until ?decisions have been made on the grading of reformed GCSEs?.

.

Fourth, that the key progress measure should be based on these eight qualifications, and calculated through a Value Added method, using end of Key Stage 2 results in English and mathematics as a baseline. This progress measure should also be part of the floor standard.

Hence the progress measure should ensure that schools are not penalised for an intake with relatively lower prior attainment:

?It will take the progress each pupil makes between Key Stage 2 and Key Stage 4 and compare that with the progress that we expect to be made by pupils nationally who had the same level of attainment at Key Stage 2 (calculated by combining results at end of Key Stage 2 in English and mathematics).?

This will ensure that each pupil?s achievements count equally:

?Pupils? scores across eight qualifications will be compared to the expectations that we have for pupils with their particular Key Stage 2 results. Progress measures give schools credit for helping all pupils, whatever their starting point. It will celebrate those schools that help children with low prior attainment achieve some good qualifications, and highlight schools in which pupils are not being stretched appropriately.?

There will be no incentive for schools to focus excessively on ?pupils near a particular borderline?.

There are no technical details of how this measure would be developed, which raises several questions.

.

Fifth, that schools should have to meet a set standard on both the threshold and progress measure to be above the floor.

The floor targets will be set in such a way that they are challenging and fair regardless of the prior attainment of a school?s intake.

.

Sixth, to ?introduce sample tests in Key Stage 4 to track national standards over time.?

Because the Government uses the same headline measures to track national standards as are used to assess schools? performance, it can be hard to see whether changes are attributable to pupils? performance or schools ?gaming? the system.

Consequently new sample tests, taken annually, might be introduced in English, maths and science, to track standards over time, building on the model established by PISA, PIRLS and TIMSS. The document asks how these could best be introduced.

.

A series of questions is also asked about possible further accountability measures:

- Whether the floor standard should be a relative measure in the first year of new exams. Because there will be relatively little data to inform the pitching of floor standards when reformed GCSEs are introduced, the consultation asks whether a relative measure might be used for the first year only, based on ?the worst performing number of schools?.

- How to publish information about the achievement of pupils eligible for the Pupil Premium. The Government plans to continue publishing ?the attainment of children eligible for the Pupil Premium, that of other children, and the gap between them? ? and in relation to the threshold and progress measures above. The consultation asks whether any further measures should be introduced.

- What other information should be made available about schools in headline measures, alongside the EBacc measure (which is a given). The document confirms that there will not be any changes to the current EBacc measure, which will continue to be published, its value lying in encouraging ?schools to offer the full range of academic subjects to more pupils?. A ?headline measure showing the progress of pupils in each of English and mathematics? is also proposed ?to show how pupils with low, medium and high prior attainment perform?. Exactly how these categories will be defined in the absence of National Curriculum levels, is not explained. These headline measures will compare schools with other similar schools ? using a ?statistical neighbours approach taking into account prior attainment? ? as well as national benchmarks. The document asks whether there are other measures that should be published (whether existing or new).

- How to recognise the progress and attainment of all pupils in the accountability system, particularly considering pupils who, as now, may not be able to access GCSEs. The document expresses an aim to publish data giving information about such pupils? progress ?wherever possible?. Further consideration will be given to how it might be included in progress measures. The consultation question asks what other data could be published for schools, including special schools, to ensure best progress and attainment for all their pupils.

- Whether the Department should no longer collect Key Stage 3 teacher assessment, whilst ensuring that the results of assessments continue to be reported to parents. The Government proposes to retain the statutory requirement to conduct and report KS3 assessments in all National Curriculum subjects, but to remove the requirement for the reporting of these results to DfE, so reducing bureaucracy. Since National Curriculum levels are going, DfE ?could only collect very limited information at Key Stage 3 in future?.

- How to recognise the achievement of schools beyond formal qualifications. The document says that ?pupils do not necessarily need to achieve a very high number of qualifications; it is not necessary to take more than 8-10 GCSEs or other qualifications to demonstrate a breadth of academic achievement?. Since schools are required to set out their curriculum online, this might be supplemented by setting clearer expectations on publication of information about ?the range of activities schools offer?. This could also be reported through the Data Portal.

.

Assessment of these Proposals

.

National Curriculum

In many respects, the revised draft National Curriculum is relatively similar to what we have now. The Key Stage structure is unchanged and there are no real surprises in terms of subject structure.

As noted above, there is huge variation in the length and detail of programmes of study, with the initial draft programmes in the primary core subjects much more specific than their predecessors and everything else stripped back to the bare minimum.

The extent of this imbalance is such that there will inevitably be pressure during consultation to reduce it, since there is no logical justification for increasing prescription in some subjects while reducing it in others (especially when academies are exempted from the National Curriculum in its entirety).

If the arguments in favour of improving flexibility and autonomy have any substance, they must surely apply as much in primary English, maths and science as any other subjects, but the Government is at risk of recreating the old National Primary Strategies under another name.

The consultation document makes clear that the Government would like to simplify the drafts even further, by removing subject-specific aims. They may even prefer to eliminate the attainment targets which are identical across all subjects and no longer serve any useful purpose.

The proposal to disapply the vast majority of the existing National Curriculum in 2013/14 is justified on the basis that it will help schools prepare for the following year when the new National Curriculum is introduced. But, if schools can cope without almost the entire structure for a year ? and even longer in some KS4 subjects ? the inevitable question arises whether they need it at all.

The revised inclusion statement deserves to be compared carefully with the current version which contains three clearly delineated sections:

- Setting suitable learning challenges ? describing how teachers should teach the specified knowledge, skills and understanding ?in ways that suit their pupils? abilities?.

- Responding to pupils? diverse learning needs ? how teachers should provide opportunities for all pupils to achieve ? and

- Overcoming potential barriers to learning and assessment for individuals and groups of pupils.

The new version does contain an explicit reference to planning lessons to reflect different pupils? prior attainment (rather than their abilities) but the statement that the obligation for those with low prior attainment is greater than the corresponding obligation to plan for those with high prior attainment appears discriminatory and unfair, for surely every learner has an equal right to their teachers? attention, irrespective of their prior attainment.

Finally, there is nothing at all in the published material about how academies ? who are not bound by the National Curriculum ? are expected to respond to it. The FAQ briefing released in June 2012 made clear the Government?s expectation that many academies ?will choose to offer it? and they also described it as a ?a benchmark for excellence?. ?Some clarity about the translation of these expectations into practice might have been included on the face of the Framework Document.

.

Key Stage Four Reform

The fundamental question is whether the Secretary of State?s change of direction is a minor adjustment or a major U-turn.

It is clear that the entire concept of a different qualification ? the EBC itself ? has been dropped, as has the plan to exert control over the supply side, by arranging for a single board to provide qualifications in each subject.

These were the two top-line features of the proposals set out in the original Key Stage 4 Reform Consultation Document and they no longer feature within the Government?s plans (although the latter will be ?kept under review?). What remains is a set of significant but nevertheless second-level plans to change the structure and content of GCSE examinations.

When he appeared before the Education Select Committee in December, the Secretary of State was asked at the outset for his rationale for the effective abolition of specified GCSEs and their replacement by EBCs, rather than confining his efforts to retaining and improving GCSEs.

His answer was as follows (these quotes are from the Uncorrected Transcript of the Session):

?We thought that it was appropriate to have a clean break with the system?

? With respect to the reason why we felt it was better to have a clean break rather than simply to continue, we wanted to ensure, first, that there was an element of innovation. We wanted to say that GCSEs, having been designed for a different world, had now had a period of time during which certain deleterious consequences had flowed from the way in which they had been designed and implemented, and we wanted to move to a new system.

We felt it would be better, if we were making the series of changes that we were making, to signal that clean break, not least the clean break between competing exam boards and a franchise system, by saying that it was a new qualification. We also felt that that new qualification would signal a higher degree of ambition overall for our education system.

Later in the same session he was asked whether he would be prepared to maintain ?the GCSE brand? since the changes he proposed could equally well be incorporated within the existing qualification, if the balance of opinions arising from the consultation supported that.

He replied:

?I have to say that it is my strong view that attempting to breathe life into the GCSE brand would be in no-one?s interest, but if I can develop a better and clearer understanding of why it is that people believe that maintaining that brand or name would be a good idea, then I would be in a better position to be able to weigh that view and decide whether or not it had merit. I have to say, it would have to be a very powerful and seductive argument of the kind that I have not yet encountered that would incline the Government to change its view on that question, but we are open-minded about what the new set of qualifications could be called.?

It is clear that the Secretary of State?s views have undergone a seismic shift since he made those responses in early December 2012.

Turning to the specific proposals for reform, the insistence on the avoidance of tiered papers appears rather to fly in the face of the consultation responses. The wording of the report on those responses ? quoted above ? is not hugely convincing.

Moreover, the Government itself has no clear alternatives beyond a common core plus extension paper model that seems almost identical in principle to a tiered approach (since someone must decide who can access the extension papers unless everyone takes them).

The reference in the Ofqual letter to the possibility ?that a range of other solutions may come forward? sounds slightly forlorn.

As for the other elements, the combined effect of plans to increase the level of challenge at the ?pass level?, improve stretch and challenge at the top end and introduce a different grading system across the board, seem to be potentially the most significant.

By ratcheting up the level of demand and changing the nomenclature of grades, any possibility of comparability between ?old-style? and ?new-style? GCSEs will be eliminated.

There is a risk that ?old-style? GCSEs will be regarded as devalued currency, while schools will have to manage a significant fall in the percentage of students achieving the top grades. This will remain a fixation in the media, regardless of efforts to shift to an ?APS8? headline measure.

It is likely that the strongest schools will cope better with the necessary adjustment, thus widening the gap between them and their comparatively weaker counterparts.

There are several loose ends, not least the ?missing? KS4 subject outlines, which should ideally have been published alongside English, maths and science as initial drafts ?for information?.

It appears that the interesting references during consultation to taking examinations ?when ready? ? rather than to a fixed timetable ? have been set aside without further consideration. This is disappointing since ?just in time? assessment would significantly increase schools? flexibility to adapt examination entrance to fit the needs of their students rather than vice versa.

Ofqual has already sent a shot across the bows in respect of the challenging timetable for implementation. The technical complexities associated with the required changes should not be underestimated and of course schools need generous lead-in times before the new courses start. A detailed implementation timeline is conspicuous by its absence.

.

Secondary Accountability Reform

The Government has rather belatedly recognised that it needs to address significant issues about primary assessment and accountability, alongside the pre-announced secondary consultation, and this leaves a significant gap in our understanding of the future direction of travel.

It would have been helpful to have had some indication of the issues that this future consultation would address.

It seems that the new-style secondary performance tables will be built around seven core elements:

- The English and maths pass grades threshold.

- The Average Point Score in eight subjects.

- Value-added progression between KS2 English and maths combined and the APS8 measure.

- Distinctions between the performance of those eligible for the Pupil Premium and other learners based on the measures above.

- A measure showing the progress made by low, middle and high attainers respectively in each of English and maths.

- Measures yet to be defined assessing the progress made by those who cannot access GCSEs (and which would be appropriate for mainstream and special schools alike).

This would suggest an interest in significantly slimming down the existing Performance Tables and the relegation of several existing elements ? such as the newly-developed KS4 ?destination measures? ? into the accompanying Data Portal.

There are important unanswered questions about how this Portal can simultaneously provide for those interested in comparing the performance of schools and for parents, interested primarily in understanding how their children have performed in comparison with national benchmarks and with their peers. It would have been helpful to have seen an outline specification.

There are also significant technical issues associated with the definition in future of low, medium and high attainers and the development of the value-added APS8 progress measure.

Although the EBacc is retained as a headline measure, there is every possibility that the new APS8 will supersede it, because it is the chosen foundation on which the core progression measure will be built. There is a real possibility that the EBacc in its current format could wither on the vine, so this is potentially another major concession from the Government.

The consequences are potentially profound, since the current menu of desirable subject choices is significantly expanded, not least to include art, music and religious education.

Meanwhile, the privileged position secured by the sciences, foreign languages, history and geography is somewhat compromised. Given their perceived difficulty for many learners, one might hazard a prediction that the take-up of foreign languages is most likely to suffer, and just when it has been made compulsory at Key Stage 2!

The potential introduction of PISA-style sampling tests opens up the possibility of developing closer links between national assessment and the existing international comparisons studies. If they wished, the Government could effectively use the current PISA methodology to monitor annual national progress.

But this raises the spectre of such sampling tests beginning to dictate the curriculum, as the Government of the day becomes increasingly concerned to demonstrate that its reforms translate into a favourable showing in PISA, TIMSS and PIRLS. Some assurances about these matters may be necessary.

.

Have all June 2012 commitments been honoured?

Despite the huge range of material that has been published, the answer is ?not quite?:

- We now have the full set of draft programmes of study for Key Stages 1, 2 and 3, albeit some months later than expected. The draft programmes of study for KS4 English, maths and science are still provisional and we lack the subject-specific content requirements for new-style GCSEs in history, geography and foreign languages.

- We have the promised consultation on curriculum aims and spoken language development across the curriculum (although the consultation document rather neglects the latter).

- There has been no second letter to the National Curriculum Expert Panel as we were originally led to expect but, more importantly,

- There is no sign of consultation on how attainment should be graded as part of the statutory assessment arrangements.

The June 2012 letter to the Expert Panel said:

?In terms of statutory assessment, however, I believe that it is critical that we both recognise the achievements of all pupils, and provide for a focus on progress. Some form of grading of pupil attainment in mathematics, science and English will therefore be required, so that we can recognise and reward the highest achievers as well as identifying those who are falling below national expectations. We will consider further the details of how this will work.?

We have reference to a new GCSE grading system, but the expectation of a new approach to grading for Key Stages 1-3 has so far been unfulfilled. It might potentially be wrapped up in the expected consultation on primary assessment and accountability, but that would presumably omit KS3.

Some clarity about the Government?s intentions with respect to this commitment is much to be desired.

.

.

Implications for High-Attaining Learners

The response within these proposals to the needs of high-attaining learners is, frankly, mixed.

The emphasis on greater stretch and challenge within the GCSE is welcome, as is the proposed new grading system, since the proportion of entries now securing A*/A grades makes the existing scale unsustainable.

The shift towards an average points score measure within the secondary Performance Tables is equally welcome, since it should hopefully remove any perverse incentive for schools to focus disproportionately on borderline candidates, at the expense of those at either end of the attainment distribution.

But the draft National Curriculum is more problematic. The huge degree of flexibility it permits could work in favour of high-attaining learners.

Schools may use such flexibility to plan and implement coherent curricular programmes ? judiciously blending enrichment, extension and acceleration ? for those who are well ahead of their peers and/or have already mastered the statutory material. (However, such flexibility will be severely curtailed in primary English, maths and science.)

The better schools will certainly do so ? whether or not they are bound by the National Curriculum ? but there is some reason to doubt whether less good schools will follow suit.

Moreover, there is currently no universal and reliable mechanism to spread effective practice from the better schools to the less good. As a consequence, the quality of curricular provision for high attainers is almost certain to be patchy ? and remain so.

Parents may be able to exercise a limited degree of market choice, but only if they are given access to relevant data in an accessible form.

Some modicum of leverage could be introduced through the National Curriculum to ameliorate this patchiness, but the levers are either under threat or have not been fully deployed:

- The draft inclusion statement rightly continues to reference the need to:

?Plan stretching work for pupils whose attainment is significantly above the expected standard.?

But this is immediately undermined by what follows: ?They have an even greater obligation to plan lessons for pupils who have low levels of prior attainment or come from disadvantaged backgrounds.? Worryingly, this falls into the trap of assuming that high-attaining pupils do not come from disadvantaged backgrounds. Furthermore, it implies low attainers are somehow a higher priority. This infringes the principle ? upheld in the shape of the new APS performance measure ? that every learner has an equal right to challenge and support, regardless of their prior attainment.

- Attainment targets have been reduced to a standard lowest common denominator which is essentially meaningless and could be removed entirely without any damage being done. But attainment targets and level descriptions were previously the basis for differentiation within the programmes of study. With the level descriptions stripped away, it is left entirely to teachers to decide how the programmes of study will be adjusted to reflect the very different needs of their pupils. In classes and schools where differentiation is already effective this is unlikely to have a deleterious effect, but in settings where high attainers are routinely under-stretched, there is no scaffolding for teachers to hold on to. The same point about dissemination of effective practice applies.

- The Secretary of State?s previous commitment to a new grading system ? in the core subjects as part of the statutory assessment arrangements ? would have gone at least some way towards filling this gap. (Schools without their own established good practice might have been expected to apply the preferred methodology outside the core subjects as well.) But consultation on grading is conspicuous by its absence. It is not clear whether it will be picked up in the forthcoming primary accountability consultation or whether it has been set aside. As I?ve pointed out on several occasions, the recent introduction of Level 6 tests (which can no longer exist in their current form beyond 2014), as well as Ofsted?s concerns about underachievement among high attainers, render this particularly important at the top end

Overall there seems a certain precarious fragility about the capacity of the current proposals to embody ?an expectation of higher standards for all children? especially those ? disadvantaged as well as advantaged ? who are not being stretched to their full potential.

The risk is much greater in relatively weaker schools because they need more substantial scaffolding to support their practice.

But ? just as Ofqual and the Education Select Committee brought about a radical rethink on Key Stage 4 reform, Ofsted is well-placed to ride to the rescue.

Their ?landmark? rapid response report on how schools teach their most able learners (though it seems not to have been announced officially) is due for publication ?in the Spring?.

It is almost certain that the remit will extend to careful scrutiny of the current National Curriculum proposals. So one would expect the recommendations directed at central Government to push for further improvements if those proposals are found wanting.

.

GP

February 2013

Like this:

Be the first to like this.

কোন মন্তব্য নেই:

একটি মন্তব্য পোস্ট করুন